Dorothy Winsor is a former English professor at Iowa State University who taught technical writing. She served as editor of the Journal of Business and Technical Communication and won six national awards for her research on the communication practices of engineers. After retiring, she turned her talent to writing for a much different audience. She now writes young adult fantasy books published by U.K.-based Inspired Quill.

Dorothy Winsor is a former English professor at Iowa State University who taught technical writing. She served as editor of the Journal of Business and Technical Communication and won six national awards for her research on the communication practices of engineers. After retiring, she turned her talent to writing for a much different audience. She now writes young adult fantasy books published by U.K.-based Inspired Quill.

You’ve written and published five young adult fantasy books since 2015. How do your stories come to you?

Usually, they’re sparked by something I read, or hear on the news, or see on TV. When I find myself thinking, “Huh, that’s interesting,” it often means that’s an idea I can twist or slide a little sideways to create something new.

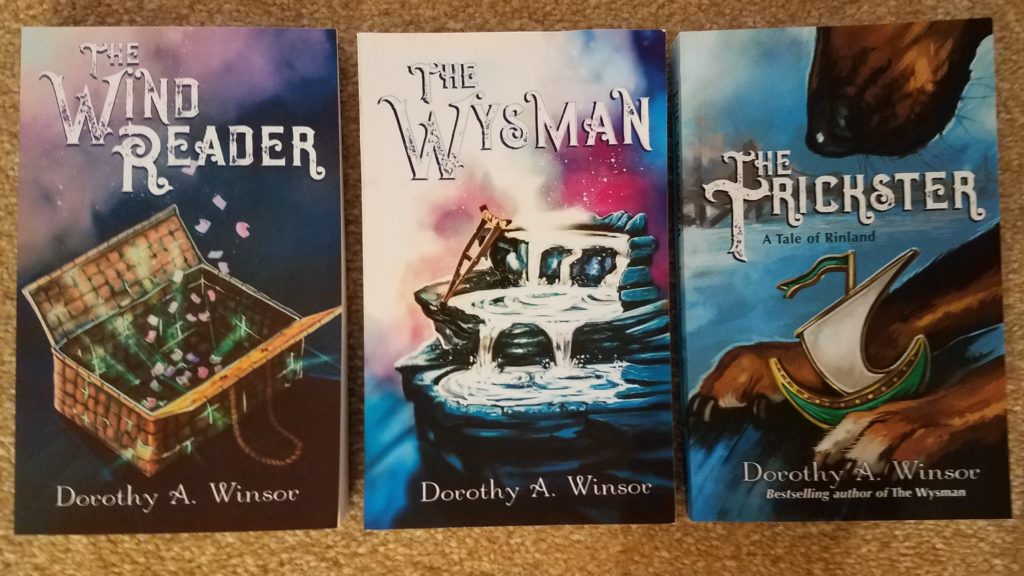

For example, I got the idea for The Wind Reader when my husband was watching the old TV show “Psyche.” That show is about a fake psychic who’s approached by the police to help solve a crime. When he succeeds in doing so, he’s stuck having to keep faking it convincingly.

I write YA fantasy and the idea of fake psychic made me think of using a fake fortune teller. My central character is marooned in a city far from home. To earn enough to eat he fakes being able to tell fortunes. Then he accidentally tells a true fortune for the prince and is taken into the castle to be the royal fortune teller, where, like the character in “Psyche,” he has to keep faking it convincingly in the midst of an assassination plot.

What do you think distinguishes your books from others written in the genre?

Writing in a genre always requires balancing some of the conventional features that draw fans with something fresh and new. That fresh, new part comes from the unique characters and plot an author creates and the thematic thread that underlies the story. For me, that thematic material usually has to do with the push and pull of family. We legitimately need the love and support of the family we’re born into or create, but they can also impose expectations that limit us. My characters often wind up working their way through that tension while an action plot is bearing down on them.

Your recently published book, The Trickster, is told in a timeless era in a place somewhere near the sea. How do you create a reliable yet imaginative setting not bound by time or place? Is the sea a metaphor for them being surrounded?

I try to picture places I’ve been and use bits of them. In the case of The Trickster, I pictured a city like New Orleans at Mardi Gras.

The idea of the sea as a metaphor never occurred to me, but it’s so good that now I think I’ll say I meant that all along.

You play with language, creating made up words such as “darkfall” and “Mage flower” that have no dictionary meaning yet are understood by the reader in context. How did you come up with those words and what role do they play?

In a fantasy novel, language is a way of world building. I make up a word or phrase when I need to talk about something and don’t want to call up images of our world. Something like “darkfall” is pretty straightforward. Readers are familiar with both halves of the word and can easily guess that it means something like “dusk.”

“Mage flower” is a little trickier. The reader may know both words but still need some explanation of what it means in the book. It’s important to work in that explanation in a natural way. It would be boring to stop the story and give a language lesson. In The Trickster, the reader would have learned in the previous chapter that a mage is a kind of magical healer. One of the characters then talks about a “dangerous herb” called “Mage flower” that makes a person suggestible. I needed an original name for the herb because I didn’t know of any real herb that would do that.

Your main characters are often strong willed young adults torn between personal loyalties and a truth they’ve discovered. Do you see yourself in your stories?

I have to assume that this material is somehow personally relevant for me or I wouldn’t keep coming back to it. But I’m not conscious of it. Maybe writing is a way for me to slip into considering this material without having to confront it head on. I find writing very satisfying. Perhaps this is why?

Which is the most sensitive topic you’ve addressed in your stories and why was it important to include it?

In The Trickster, one of the central characters, Dilly, is a sexual assault survivor. She was groped by her mother’s boyfriend. To add to her pain, when she told her mother about it, her mother didn’t believe her. I think this, or something similar, occurs often enough that it’s worth including so the story feels honest and any reader who’s been similarly assaulted feels recognized.

What do you hope your readers take away from your books?

First, I hope they’re entertained. To me, that’s the minimum we owe our readers. But then, I hope the story is deep enough that they wind up thinking about it afterwards. Stories are a way we try on other lives. They help us not only to understand our own lives, but also to empathize with the lives of others.

What’s the most difficult part of your writing process and how do you overcome it?

Writing a first draft is incredibly painful for me. I love revising. I could do it forever as I think of ways to deepen characters and increase the tension in the plot. But that first draft is scary. The only way to overcome it is to do it. I set a work schedule for myself and stick to it. I remind myself that I’ve felt this way before and come out on the other side.

You’ve written on your blog about the benefits of critique groups. Will you summarize your thoughts on being critiqued as well as critiquing others?

I find it enormously useful to see other people react to my writing. I’m too close to recognize what’s working versus what needs to be reconsidered. It’s especially telling if more than one person has the same reaction.

It took me longer to realize how much I was learning from critiquing other people. Giving useful feedback to someone else requires me to be really thoughtful. For instance, I need to notice if my attention is wandering and try to analyze why. Once I’ve noticed and named an issue in someone else’s work, it’s easier for me to see it in my own too.

Why have BWW members critique your manuscripts when they are not your target audience?

First, I want to point out that the audience for YA is wider than many people assume. It’s estimated that more than half of YA books sold are read by adults. Especially in fantasy and science fiction, the line between YA and adult books has always been blurry.

Having said that, of course I want BWW members to critique my manuscripts! They’re perceptive, knowledgeable readers who can give genuine, informed help. Critiquing well is hard. In my experience, BWW members can do it.

Do you have an agent that represents your work? If so, how did you find that agent?

I used to have an agent. I found her through cold querying. At the moment, though, I’m operating without one. I’m currently published by a small press, and for that, you don’t need an agent.

Your publisher is outside of the U.S. Any challenges with that?

Not really. My editor and I have to work around time zones when we have Skype conferences, but that’s pretty easy to manage.

How have your readers responded to the stories?

I love seeing their reactions on Goodreads or Bookstagram. Those vary from trivial to weighty. With The Trickster, they often talk about how much they love the dog in the book. With The Wysman, the previous book in the series, they almost always mention how much they appreciate that the boy central character is disabled.

Why write a blog?

I’m not gonna lie, my editor told me I had to. Well, not really had to, but she advised me to do it. Readers these days want to feel connected to writers. A blog is one way to be available to them. I’ve been blogging twice a month for several years now, mostly about writing, and I usually enjoy it.

However, I strongly suspect that social media is in the process of replacing blogs as the favored way for readers and writers to connect. I confess to loving twitter.